Main Highlights:

- A Redesign from the Top Down

- Meriden kept on wagering on the actual school day.

- The fact that the kids appear interested and even have fun is beneficial.

- In the world of education, it can take a lot to make even a small difference.

A Redesign from the Top Down

Late 2019 saw the start of the changes in Meriden.

After assisting in the turnaround of one district school that was in danger of being taken over by the state due to subpar performance, Mr Crispino, a former principal, was appointed to oversee all elementary schools. After the school received a prestigious national award, Mr Crispino was requested to teach the lessons to the entire district.

The pandemic then broke out.

By the fall of 2020, Meriden had already resumed operations, which was a decision that undoubtedly served as a safeguard against more significant academic losses. Nevertheless, a lot of families chose to remain at home, including those at Franklin, where some students stayed away for several months.

Schools across the nation have tried to add instruction to make up for lost learning, though frequently outside of the school day, during after-school tutoring or summer school. The success of these initiatives depends on student participation.

Meriden kept on wagering on the actual school day.

In order to devote more time to math, district officials diverted a half-hour that was intended for students who needed extra assistance in a variety of subjects from teachers or worksheets.

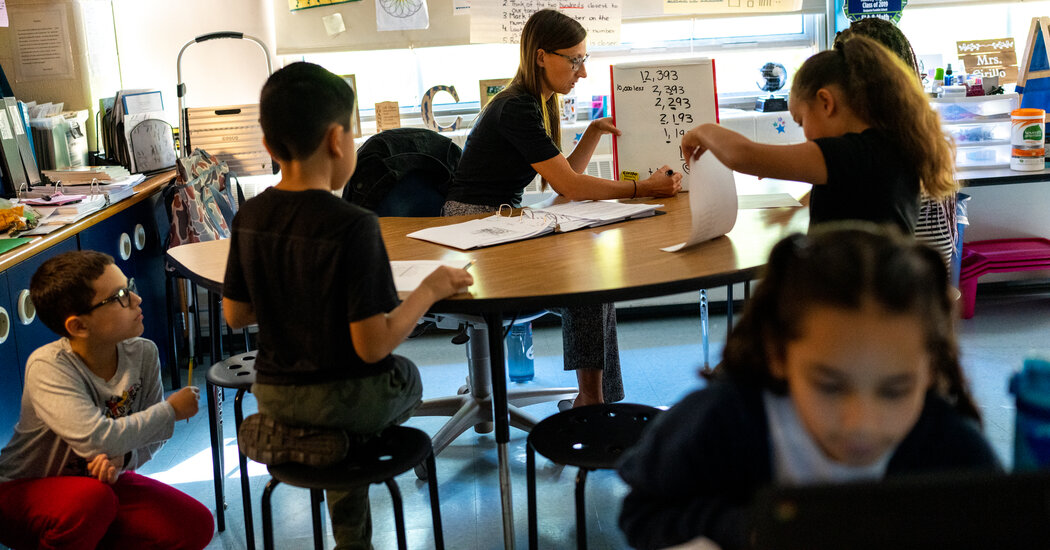

Math is now taught at Franklin in a consistent manner: a brief lesson is followed by group work. While some students work in their own groups for the next 15 or 20 minutes, the teacher meets with the others. Tutors, some of whom were paid for with federal pandemic relief funds, are used by students who need extra assistance.

Students turn around when a buzzer or chime sounds.

Working with students in small groups is “really important,” according to Julie Sarama, an expert on early math education at the University of Denver, but many teachers past kindergarten don’t want to do it. She claimed that tradition plays a role in some of the resistance. “You merely instruct as you were instructed.”

Changes at Franklin depended on its 350 students adhering to a strict schedule. Along with Mr Crispino, the school’s principal Joanne Conte observed classrooms. Since that five minutes equated to lost instructional time, even a five-minute delay in getting back from recess could be noticed.

That’s 25 minutes a week, according to Mr Crispino.

Feedback was frequently left to Ms Conte, who saw herself as the tortoise, “slow and steady,” to Mr Crispino’s energetic hare. She left questions or compliments in the mailboxes of teachers in the form of handwritten notes.

Another change asked teachers to cover the same material per grade at the same rate. The strategy ensured uniformity but also reduced teachers’ control over their classrooms.

For Halloween, Christine Joy’s fifth-grade students eagerly anticipated her arrival with pumpkins for them to weigh, measure, and experiment with. She must plan ahead and reserve “flex” minutes under the new structure because she is unable to simply teach the lesson when she feels like it.

Some teachers initially viewed the new system as being overly regimented, adding extra work, and taking the fun out of teaching, according to Krista Vermeil, a teacher at Franklin and a vice president in the teachers’ union in Meriden, which worked on the changes.

Any kind of change feels very personal because we put our whole selves into what we do, she said.

She continued, “I think the buy-in is there now,” though.

The fact that the kids appear interested and even have fun is beneficial.

Recently, eager fourth graders raised their hands to share their methods for mentally resolving the equation (15 + 16 = 31). Students spread out on a beanbag chair or carpet while teachers met in small groups.

Marcus Crespo-Ellison and Brielle Betancourt, a 9-year-old girl with long, dark hair and a soft voice, worked together. They realised that practising together had benefits. You could support one another, Brielle said. You can pick up knowledge from various people.

Marcus, who is 9 years old, surprised everyone by claiming that math was his favourite subject. He admitted, “I kind of like math. I’m very proficient in math.

According to experts, peer work can be especially helpful in math, which is brought to life through the mystique of problem-solving. Students can exchange problem-solving techniques with one another during lessons rather than getting frustrated or, more problematically, bored.

According to research, adding more class time and tutors to the school day can also be beneficial, but these strategies must be used well.

Tequilla Brownie, the chief executive of TNTP, a nonprofit that works with school districts and has urged schools to focus less on reviewing previous material for struggling students and more on starting with grade-level content and filling in gaps, declared that “more time wasted is just more time wasted.”

In order for students to reason and apply math in the real world, math experts emphasised that lessons must place a strong emphasis on conceptual understanding rather than merely regurgitating correct answers.

Fifth graders at Franklin may be required to plan a Thanksgiving meal on a budget for their families, weighing options and making decisions.

The fifth-grade teacher, Ms Montano, instructed the students, “Let’s say the turkey is 89 cents a pound; they have to figure out how many pounds they need.” You want to make mashed potatoes. Will you be purchasing fresh or boxed potatoes?

And still…

The development at Franklin in some ways also highlights the challenging work that needs to be done.

In English language arts, the school is still catching up. That subject, which historically had better student outcomes and already had small-group instruction and 90-minute classes for the majority of grades, underwent fewer changes.

The disparities that characterise American education still exist, even in math. For instance, at Franklin, Hispanic students lag behind white students while lower-income students lag behind their higher-income peers.

Although they have not caught up as quickly, other Meriden schools that also changed the way they taught are making progress.

It’s challenging to figure out the causes. Schools vary in size and poverty levels. Then there is school culture, a mystical quality that is challenging to measure but is evident in fist bumps and hugs in the hallways as well as yoga poses and breathing exercises done before classes.

In the world of education, it can take a lot to make even a small difference.

Meriden’s superintendent, Mark Benigni, has recently been daydreaming about what might be conceivable if schools had more time in the day.

Some educational leaders have argued that school districts should lengthen the school year or day to make up for pandemic losses. This strategy would require not only political will on the part of educators and parents but also financial resources and staff, which are priceless in the field of education.

Six hours and 180 days are insufficient, according to Mr Benigni. It has never been sufficient.