Main Highlights:

- Yacovone chooses to write a book about history textbooks; why?

- What urban legends were you attempting to dispel with this book?

- How does his work set the debate over whether critical race theory should be taught in school in context?

A new book aims to provide some frame of reference for how history textbooks historically originated to focus on the observations of white Americans and downplay those of Black Americans at a time when there is a political discussion over critical race theories and how much of America’s least desirable moments should have been taught in American schools.

Donald Yacovone, a researcher at Harvard University, examined 220 history textbooks from 1832 to the present in his book Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity, which was published on September 27.

One of his most important realisations was that textbooks tended to be heavily biased toward national politics. The stories of African Americans were frequently ignored because they were underrepresented in that field. Yacovone informs us that “there is a very limited knowledge of what history is.”

Yacovone discusses the most unexpected facts he discovered in these textbooks in this article. He also discusses how the books are a window into how America is portrayed to the future generation of leaders.

You choose to write a book about history textbooks; why?

YACOVONE: I don’t want people to believe that I’m some disgruntled leftist from the 1960s who hates America and is attempting to get it. I am not that. That’s not really how the book came to be, either. It was entirely unintentional. I was composing a different book.

I only needed a quick break, so I made the decision to visit the Harvard Gutman Library at the School of Education and look through a few history textbooks to see how they handled the abolitionists. I didn’t know what I was walking into, to be honest.

I visited the library’s Special Collections Division, which is now closed, where Rebecca Martin, the division chief, gave me a tour of their extensive collection of over 3,000 textbooks. And I was simply in awe. They must have this collection, I had no idea.

Did you notice a unifying thread in these textbooks as a whole?

They all viewed the integration of African Americans into American society as a “problem,” by a wide margin. The “problem of a Negro” and how much he needed to be controlled because he was so incompetent and ignorant became the dominant theme of American history textbooks as the 20th century progressed.

This idea was practically Evangelical in nature. Wow, I thought as I browsed over the entire collection. This isn’t really a textbook study, though. Because textbooks are written with the intention of inculcating young people with American ideas, a sense of their place in the world, and an understanding of what is respected and cherished in this country, it is a study of national identity.

That it is a white man’s world was what these publications were asserting well into the 1960s.

How were historical facts distorted in these textbooks?

Reconstruction was deemed a grave mistake by textbooks written in the early 20th century because it attempted to raise Black people who lacked the intellectual capacity to govern to a position of social participation. They required subjugation. From 1900 until the 1960s, this becomes the dominant theme of virtually every textbook.

Nat Turner, who organised an uprising of slaves in Virginia, represents either a justifiable form of opposition to slavery or clear danger to white supremacy. Either John Brown was a violent, deranged anarchist who started the Civil War, or he was a hero who stood for the impossibility of slavery persisting.

John Brown organised a raid with abolitionists against the American armoury at Harpers Ferry. He was portrayed in an overwhelming majority of textbooks as being insane, dangerous, and a menace to the Republic—the key factor that led to the Civil War. As a result, the emphasis is shifting from Northern agitation, particularly that of John Brown, to the South’s defence of slavery as the primary cause of the Civil War.

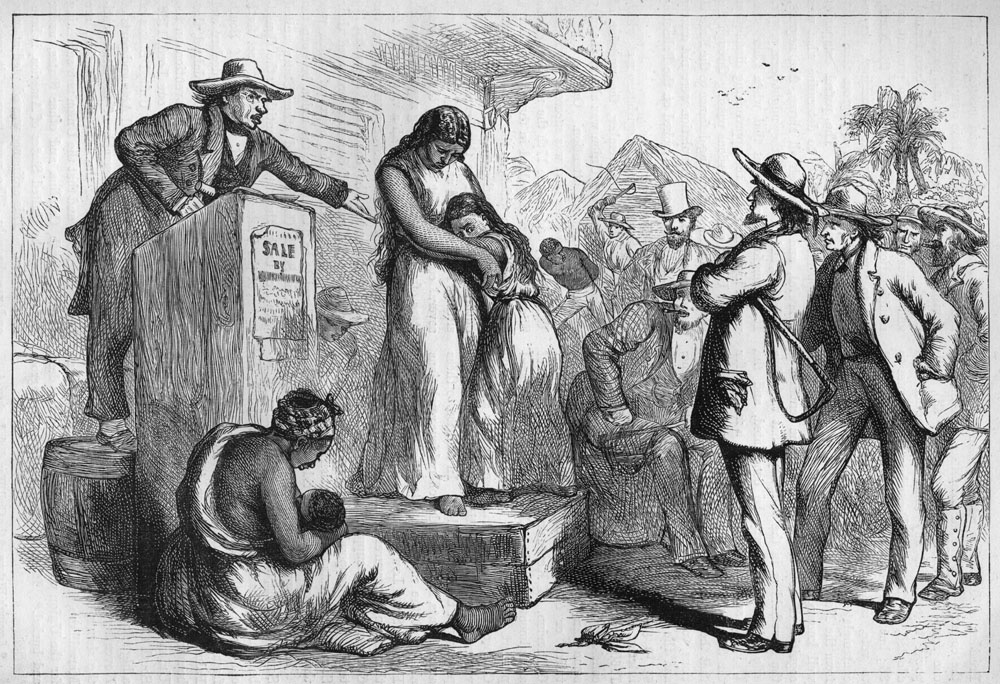

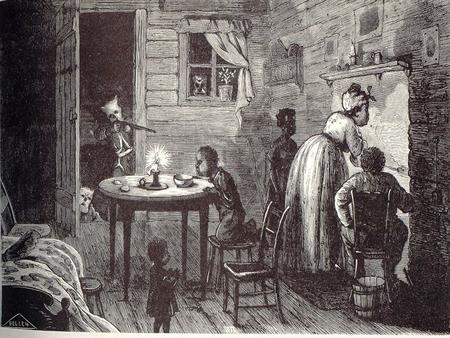

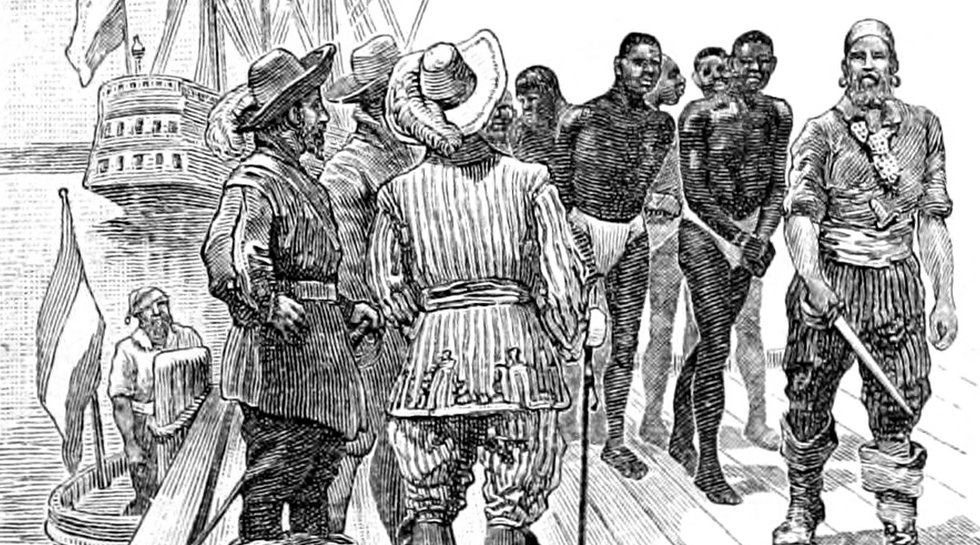

One is surprised by how few illustrations of African Americans there are in textbooks from the pre-Civil War era. People of African heritage were simply not included in these texts since they weren’t seen to be essential. Almost all of these textbooks only mentioned the introduction of slavery in Virginia in 1619 for one or two phrases. They talked about the importation of unmarried women as wives of white settlers for a lot longer than they did about the introduction of slavery.

You mention John H. Van Evrie, a 19th-century New York editor who is referred to as “the nation’s first professional racist.” Why did you centre your book on him?

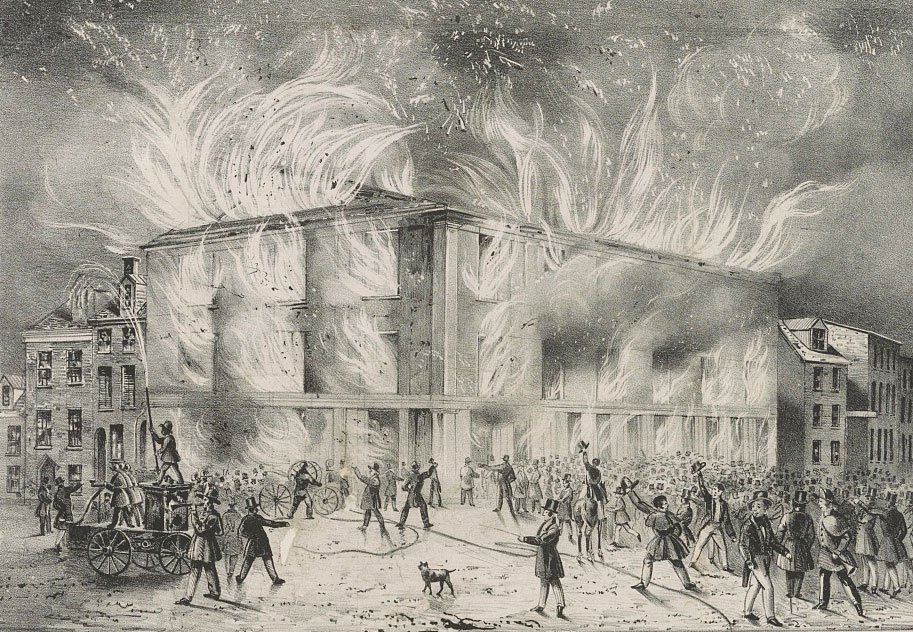

Where does it originate from? I asked after reading about white supremacist views in all of these textbooks. I studied digitised newspapers all summer long and discovered Van Evrie’s mentions all over the place. He published adverts in 1,400 different American newspapers in a single year.

In Manhattan, he built a little empire that included publishing his own books, many pamphlets, poetry, and two newspapers that were read by thousands of people. His main message was the need for African Americans in American society since, in Van Evrie’s opinion, they were created to carry out the tasks of the white man.

He was created by God and nature to carry out the tasks of the white man. My reading of the textbooks confirmed every point he made.

What urban legends were you attempting to dispel with this book?

The main one is the North’s role in the development of white supremacy. It is a white Northern creation, not a Southern one. It is a problem in America. The vast majority of Americans reside elsewhere than in the South.

Boston, New York, and Chicago saw a brief period of expansion in the publishing sector. The distribution network was controlled by those cities. More than 90% of the authors who created these textbooks were either born in the north or had received their education there.

The myth that the Civil War was fought for states’ rights rather than slavery, popularised by the Lost Cause narrative, is widely believed to have originated in the South, but your book demonstrates that publishing houses in the North also produced a large number of books about the Confederacy’s Lost Cause.

The fact that the initial manifestation of the Lost Cause ideology originated in the North rather than the South genuinely astounded me. The Daughters of the Confederacy, renowned for supporting segregation and the Lost Cause, well, guess what? They reprinted who? Van Evrie, John H.

How does your work set the debate over whether critical race theory should be taught in school in context?

To avoid having a difficult conversation about race and racism, Trump supporters invented this phenomenon, which doesn’t actually exist. That’s not what they want. This is a sign of the psychological crisis that many white Americans are going through as a result of how American culture is changing.

And this opposition to historical instruction is one of the main responses. This is real information, not fiction. Slavery does exist. Real racial dominance exists. However, they are making every effort to disprove it and maintain the purity of innocence. Additionally, it won’t succeed.