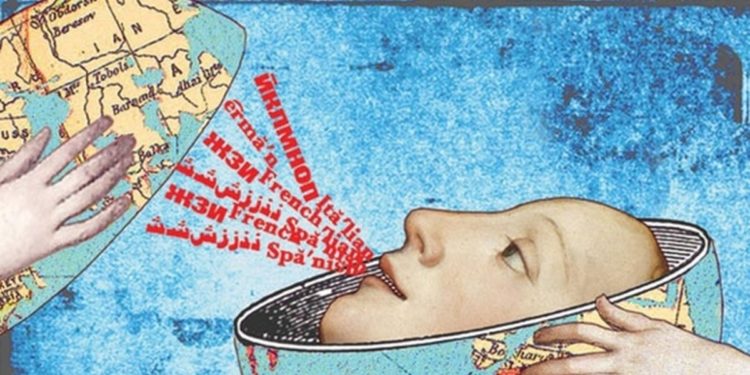

Mother tongues are getting threatened in a globalising environment where Hindi and English are commonplace. They are neither acknowledged by the government nor taught in schools.

People who speak minority languages, also known as “mother tongues,” are either too old or unwilling to pass them on to their children. Discrimination based on language, among other factors, is a common source of human rights abuses in India, though it is generally overlooked.

Because linguistic minorities are gradually abandoning their home tongues, our linguistic diversity is in jeopardy. This, combined with the government’s apathetic attitude toward language preservation, has given India the dubious distinction of having the world’s highest number of endangered languages.

English has been appointed the primary medium of instruction in all public and private schools in two states: Jammu & Kashmir and Nagaland. In current state schools, more and more states, including Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Delhi, are introducing English-medium options.

Private English-medium schools are a burgeoning market, with services ranging from roughly Rs200 per month to over Rs2 lakh per month. The assumption that English is a quick-fix answer is the driving force behind India’s tremendous drive for it. A magical phrase.

There is only one way out. It appears that English will bridge the skills gap, provide job possibilities, and set the country on the route to greatness. Private schools now educate about a quarter of all Indian youngsters. Officially, a large percentage of these institutions are English-medium.

As a result of this transition, states like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have begun to offer an English-medium alternative in existing government schools in the hopes of halting the flow of children from public to private schools.

The survival odds of a language are determined by whether or not it makes it to the ES. Schools in non-Hindi speaking states are required to teach a language listed in the ES in addition to Hindi and English. The “Three Language Formula” is a government of India education programme that was implemented in 1968.

(TLF). TLF, on the other hand, does not mandate that non-scheduled languages or mother tongues be taught in schools. “What occurs mostly in long run is […] people can’t express themselves in their mother tongue because certain terms have been lost, so they switch to the dominant language.

Educators, educationists, and linguists around the world, including in India, agree that children learn most successfully in their mother tongues. According to UNESCO research, “children who begin their education in their mother tongue make a better start and continue to perform better than those who begin school in a new language” have a better start and continue to perform better.

Another impediment for pupils learning the regional language is that in order to teach and learn a language, teachers must be highly knowledgeable in the languages they teach.

Multilingual teachers are required in primary schools, where one teacher teaches all subjects. Apart from the challenges with the language pedagogy commonly utilised in Indian classrooms, such teachers are hard to come by.

As a result, we must consider the following questions: What do we lose when we lose a language? What do parents lose when they don’t speak their native language to their children? Is it possible for a way of life to come to an end? And does it make a difference if a new one starts? Is it more important to have a linguistically diverse country with 1,635 mother tongues or a nation with 122 languages?

Also Read: 5 Biographies you should read: