Main Highlights:

- Abstracts’ definition and function

- The Abstract’s Contents

- The Best Time to Write an Abstract

- Verb Forms to Use in Your Abstract

- Samples

Abstracts’ definition and function

An abstract is a succinct summary of your research paper (published or unpublished), typically around a paragraph long (roughly 6-7 sentences, 150–250 words). A strong abstract accomplishes a number of things:

- An abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper.

- It also helps readers remember important points from your paper.

- An abstract enables readers to quickly grasp the gist or essence of your paper or article, allowing them to decide whether to read the full paper.

It’s important to keep in mind that search engines and bibliographic databases identify key terms for indexing published papers using abstracts in addition to titles. Therefore, the information you provide in your title and abstract will be crucial in assisting other researchers in finding your paper or article.

Your professor may give you specific instructions on what to include and how to organise your abstract if you are writing an abstract for a course paper. Similar to this, academic journals frequently have particular specifications for abstracts. You should therefore be sure to look for and abide by any instructions provided by the course or journal you are writing for in addition to the advice on this page.

The Abstract’s Contents

The majority of the information listed below is condensed into abstracts. Of course, you will elaborate on and clarify these concepts in much more detail in the body of your paper.

The amount of space you give to each type of information in your abstract—as well as the order in which you present it—will vary depending on the type of paper you are summarising in your abstract. You can see examples of this below. In some instances, this information is implied rather than explicitly stated.

For various types of papers, including empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies, the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, which is widely used in the social sciences, provides detailed instructions on what to include in the abstract.

The following types of information can generally be found in abstracts:

- The context or background information for your study; the broad subject under investigation; and the particular subject of your study.

- The key issues or claims of the issue your research seeks to solve.

- What is already known about this issue, what has previous analysis produced or demonstrated?

- Why is it important to answer these questions, including the primary cause(s), the necessity, the justification, and the objectives of your research? Are you, for instance, researching a new subject? Why is that subject relevant to study? Are you addressing a hole in earlier research? applying fresh approaches to reevaluate ideas or data that already exist? settling a disagreement in your field’s literature?

- Your analytical and/or research strategies

- Your primary conclusions, findings, or arguments

- Your findings’ or your arguments’ significance or ramifications.

Without the reader having to read your entire paper, your abstract should be understandable on its own.

Additionally, you don’t typically cite references in an abstract; instead, the majority of it will be a description of the material you looked at for your research, the results you found, and the main points you made in your paper. The specific literature that supports your research will be cited in the paper’s body.

The Best Time to Write an Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will be the first section of your paper, it is best to wait until you have drafted your entire paper so that you are aware of what you will be summarizing.

Following are some examples of abstracts from papers or articles that have been published; all were written by UW-Madison faculty members who represent a variety of academic fields. To help you see the work that these authors are doing in their abstracts, we have annotated these examples.

Verb Forms to Use in Your Abstract

The present tense is used in the social science sample (Sample 1) below to discuss general truths and interpretations that have been and are still valid, including the leading theory for the social phenomenon under investigation. The methods, results, arguments, and implications of the findings from their new research study are all described in that abstract in the present tense. The past tense is used by the authors to describe earlier research.

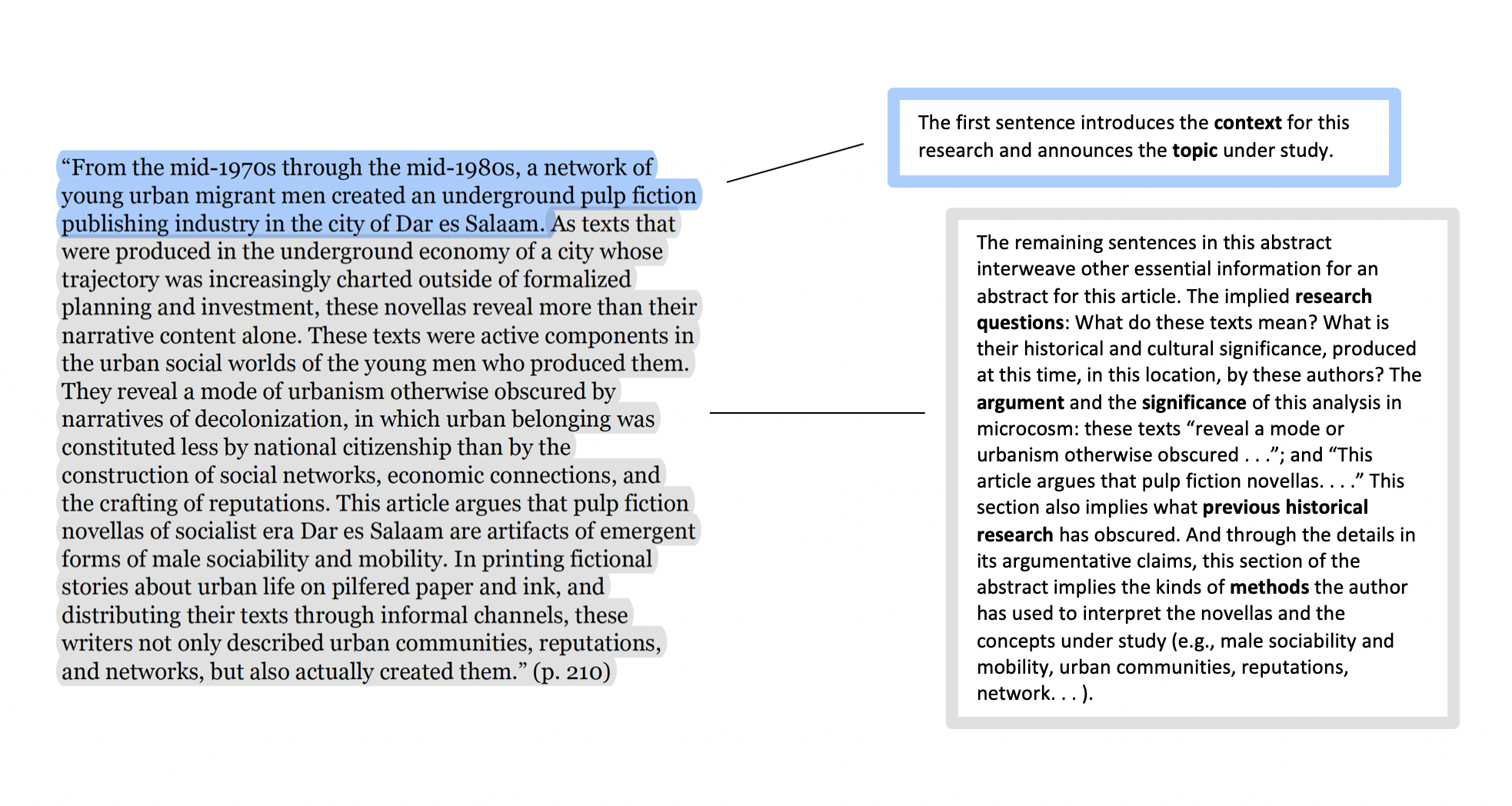

The following humanities sample (Sample 2) uses the present tense to describe what is happening in the texts, to explain their significance or meaning, and to describe the arguments put forth in the article. The texts are works of pulp fiction that were written in the 1970s and 1980s.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below describe what previous research studies have done as well as the research the authors have conducted, the methodologies they have used, and the results they have found in the past tense. They use the present tense in their justification or justification for their research (what needs to be done).

Additionally, they explain the importance of their study by using the present tense (in Sample 3, “Here we report…”) and introducing it (in Sample 3, “This reprogramming… provides a scalable cell source for…”).

Sample Abstract 1

Social science-based

Presenting fresh research on the causes of spouses’ growing economic homogamy

“Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” by Pilar Gonalons-Pons and Christine R. Schwartz. pp. 985–1005 in Demography, vol. 54, no. 3, 2017.

Sample Abstract 2

By way of the humanities

This article analyses underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania and presents a case for their cultural significance.

Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975–1985 is a study by Emily Callaci. 183-210 can be found in Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 59, no. 1, 2017.

Sample Summary/Abstract 3

From the sciences

A new technique for converting adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells is described.

Pratik A. Lalit, Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary 18, 2016, 354–367 in Cell Stem Cell.

It should be noted that this journal refers to the opening paragraph of the article as a “Summary” rather than an “Abstract.” This journal offers readers a variety of ways to quickly understand the content of this research article. This article has a two-sentence “In Brief” summary, a bulleted list of highlights at the beginning of the article, a powerful graphic abstract, and a paragraph-length prose summary.

A Structured Abstract, Sample Abstract 4,

Scientific fields

Reporting findings from a carefully monitored study on the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in treating acute bacterial sinusitis

Authors must adhere to strict word limits and divide their abstract into four distinct sections for this journal. We did not add annotations to this sample abstract because the headings in this structured abstract are self-explanatory.

Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children, by Ellen R. Wald, David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. 2009, p. 9–15 in Pediatrics, vol. 124, no. 1.

Abstract

“OBJECTIVE: There is debate over the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in treating acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children. This study sought to evaluate the efficacy of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the management of ABS in young patients.

METHODS: This study used a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled design. Participants had to be between the ages of 1 and 10 and have a clinical presentation consistent with ABS. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg), or a placebo after being stratified by age (6 or 6 years) and clinical severity.

On days 0 through 30, symptoms were surveyed on days 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 30. On day 14, patients were examined. According to the scoring guidelines, children’s conditions were classified as cured, improved, or failed.

RESULTS: Of the 2,133 kids who had respiratory issues and were screened for enrollment, 139 (6.5%) had ABS. 56 patients were chosen at random from a group of fifty-eight patients. 6630 months was the median age. Six patients (11%) and fifty (89%) patients, respectively, presented with nonpersistent symptoms.

The illness was categorized as mild in 24 (43%) of the children and severe in the remaining 32 (57%) of the children. 14 (50%) of the 28 kids who received the antibiotic were cured, 4 (14%) showed improvement, 4 (14%) had treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Four (14%) of the 28 kids who received the placebo were treated successfully, five (18%) made improvements, and 19 (68%) of them failed the course of treatment.

Compared to kids who received the placebo, those who received the antibiotic had a higher chance of being cured (50% vs. 14%) and a lower chance of experiencing treatment failure (14% vs. 68%).

CONCLUSIONS: A common side effect of viral upper respiratory infections is ABS. According to parental reports of time to resolution, amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate significantly increases cure rates and decreases failure rates compared to placebo.